LESSON 1

History’s Cut Up: The Story of Andreas Vesalius, who dissected human bodies, which annoyed his teacher, but reshaped the study of anatomy.

Imagine a world where transportation means riding a horse or climbing onto an ox-pulled wagon, where communication means shouting or writing a letter and hoping that the person who gets it knows how to read. Our world may be very different, but people weren't that different from us, and they had to deal with many of the same problems we have today. For instance, a pandemic in Renaissance Italy changed Leonardo da Vinci's life, and world history too. While people in the past didn't have all the history and scientific knowledge that we have to learn from, they were just as smart as we are, but also made many of the same mistakes. Here's a story from the 16th century that began a process that led to modern medicine. If you want to do some follow up learning work, some suggestions follow the story:

|

Johannes Guinther sits in a throne-like chair at the University of Paris (later to be called the Sorbonne); he is reading aloud from a masterwork on the anatomy of the body, written by the great Roman physician Galen. Medical education in Europe is built on Galen's writings and Guinther’s translation is said to be the best there is. Those who listen to the professor intend to be doctors.

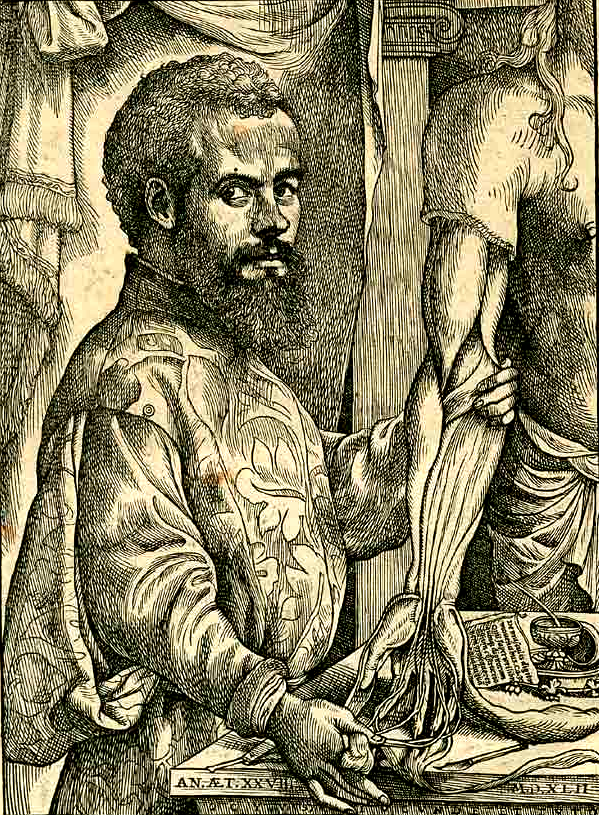

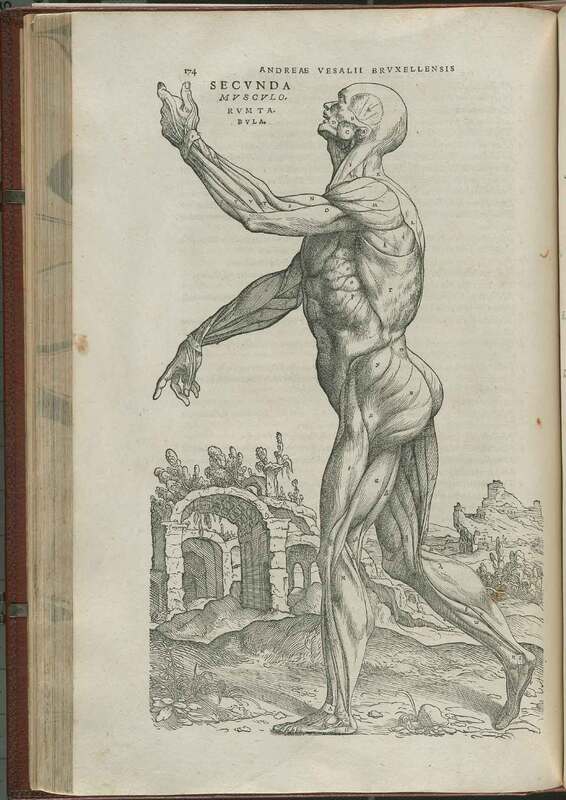

It is 1534 and thanks to Guttenberg and his printing press (now almost 100 years old) books have become widely available in Europe, but not so widely that every student can have his own copy of Galen. As the professor reads, a surgeon cuts into an animal, perhaps a dog. An instructor uses a stick to point out body parts. Neither professor nor instructor gets blood on his hands. It is the surgeon, often a barber, who is bloodied. Once a year the dissection is of a human, but the rest of the year it may be an ox, or a sheep, or a dog that gets sliced. A 20-year-old medical student, Andreas Vesalius, is among Guinther’s students. His father is royal apothecary to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. His British mother is an educated woman from a family of physicians. Vesalius speaks, writes, and thinks in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, as well as French and English. He also thinks for himself and he is not impressed with the esteemed professor or the way he is being taught. Vesalius has been dissecting mice and small animals since he was a kid; he has extraordinary skills when it comes to using a knife and he wants to dissect human cadavers. As it happens, Paris is filled with dead bodies; thieves and other criminals get strung up on street corners. So, he scrounges cadavers and does his own dissections. When some teachers and students hear what he is doing they ask him to cut into a human corpse and explain its parts to them, which he does. This does not please the renowned Johannes Guinther; especially when Vesalius finds errors in the revered Galen’s work. (Galen lived in Rome in 200 AD/CE, which was 13 centuries before Guinther. Galen mostly dissected oxen and monkeys. Human dissections were forbidden in ancient Rome.) In 1536, when war breaks out between France and the Holy Roman Empire, Vesalius is forced to head home. There, at the University of Leuven (Louvain), he does what is said to be the first human dissection performed in Belgium in 18 years. Does he go too far with his corpse stealing? We don’t know. We do know that Vesalius leaves Belgium for the University of Padua. It is a good move. Italy, at the center of one of history’s great inventive moments, is generating creative minds. Renaissance artists are way ahead of the academics. In Padua Vesalius continues his dissections, often before large audiences. The day he receives his doctorate in medicine, he is asked to stay at Padua, now as Chair of Surgery and Anatomy. A judge will provide him with bodies of executed criminals. Sometimes executions are timed to coordinate with his lectures (there is no refrigeration). Vesalius has the dead body hung from a beam in the lecture hall, a rope acts as a pulley. As he cuts into the corpse he points out body parts. His classes are jammed with practicing physicians as well as university students. What they see often contradicts the long-dead Galen’s words. Vesalius writes, “Galen was deluded by his dissection of ox brains and described the cerebral vessels, not of a human but of oxen. . . Aristotle in particular, and quite a few others, thought that the nerves took origin from the heart. . .Galen never inspected a human uterus.” Vesalius hires an artist from Titian’s studio to do eleven large detailed teaching charts drawn from human cadavers he has dismembered. The drawings are works of art, as well as works that picture anatomy, they are hugely successful. Vesalius intends to reach a still bigger audience with a published book, and he has a model to follow. He knows that Leonardo da Vinci and Marcantonio della Torre spent decades collaborating on a masterwork detailing the human body. Della Torre, a professor of anatomy at the University of Padua, wrote text. Leonardo did thousands of drawings. A womb he drew holds a fetus. His is the first accurate depiction of the human spine. But della Torre falls victim to the plague that sweeps Italy in 1511. Political turmoil follows the plague. Leonardo finds refuge in the Vatican in Rome, where both Michelangelo and Raphael are at work. In 1516, Francis I of France invites him to live in a chateau in Amboise (later hometown of Louis Pasteur); Leonardo heads there taking some of his anatomical drawings with him (others are left in Padua). Then the record gets fuzzy. Most of his scientific notebooks disappear until, in the 19th century, some 600 drawings are discovered packed away in the royal collection in London. Did Vesalius see any of Leonardo’s drawings? We don’t know. He almost certainly was aware of those drawings and of Leonardo’s intent to detail the human body. Leonardo has been dead for 24 years when, in 1543, Vesalius publishes a seven-volume masterpiece: De humani corporis fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body, often known as Fabrica). An illustrated study of the human body, it combines anatomical insights with stunning artistic renderings. That same year Copernicus’s great work on astronomy is published in Poland; these two books become foundation stones for a “Scientific Revolution” that will begin a half century later when Giordano Bruno and Galileo Galilei initiate a new kind of intellectual questioning. But that is in the future. In the 16th century, most physicians, especially Johannes Guinther, can’t handle Vesalius’s criticism of Galen, who is said to have been divinely inspired. Now the story gets muddy, but someone, probably someone with clout, suggests that Vesalius make a trip to the Holy Land, perhaps as a kind of penance. He does, his ship is destroyed during a storm in the Ionian Sea and Vesalius dies on the island of Korfu: it is 1564 and he is fifty years old. For further learning: Define:

The plagues were major historic events, in the 16th century they arrived every few years, sometimes killing as many as one person in every three. Writing prompts:

|

How does life work? Is there a plan? Is it common to all animals? How about plants? Could there be a connection between them? Those questions may have been asked by the first humans. But scientific thinking, based on observation, experimentation and proof, is a modern thing. You can place Christopher Columbus among its dads.

Writing about his big voyage, history’s intrepid sailor said, “Although there was much talk and writing of these lands, all was conjectural, without ocular evidence . . .those who accepted the stories judged by hearsay, rather than on tangible evidence.” Hearsay? Ocular evidence? University study in 1492 focuses on works of the ancients (especially Aristotle) it does not include direct observation. But sailors deal with real winds and real currents. So, while his Renaissance peers are creating artistic wonders often based on antique works, they are also planting questioning seeds that will grow to uproot the lock the ancients have had on learning. Leonardo da Vinci is among those doing the planting. He performs at least 30 human dissections (often by candlelight and clandestinely). He learns human anatomy firsthand at a time when medical school dissections are mostly of dogs and oxen. Wanting to understand the human eye, Leonardo hard-boils one, which allows him to cut it with extraordinary precision. Galileo, born a half-century later, will bring both new tools and new concepts to a world struggling to find its way into modernity. As for questions about life, its origins, and how it works: we now know that all life forms grow and develop by following coding instructions found in giant molecules we’ve named DNA and RNA. Amazingly, we have learned to read that life code; the same code that is used to provide information for your cells and also for those of a turnip. This is chapter is excerpted from a new series on life science to be published. These lessons are intended for your use at home. They are copyrighted by Joy Hakim and are not for commercial use or redistribution.

|