Lesson 14

On Keeping A Journal:

Which Could Make You Famous, as it Did For Two 17th Century Diarists

On Keeping A Journal:

Which Could Make You Famous, as it Did For Two 17th Century Diarists

|

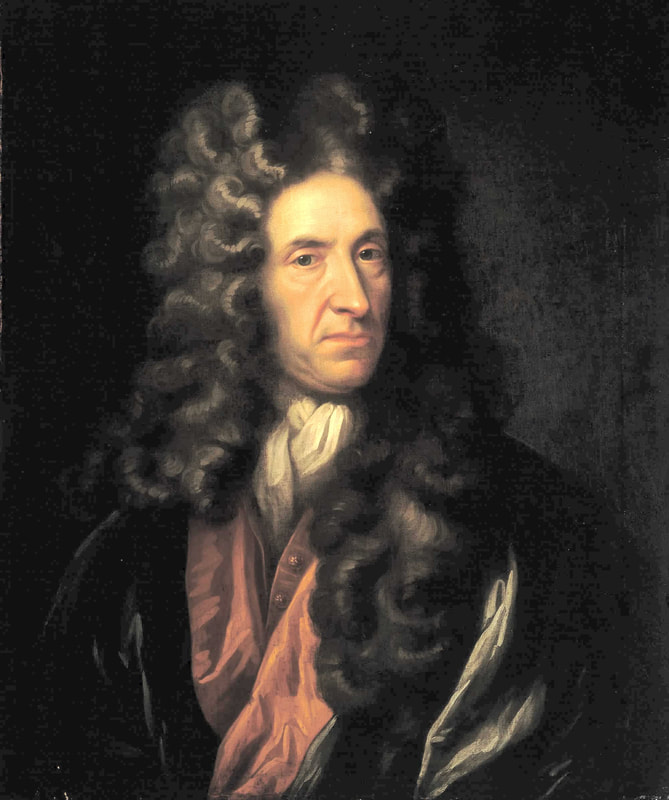

It is 1665 and the bubonic plague is spreading through London. And two journal writers, Daniel Defoe and Samuel Pepys, are there to tell the story of what happened. Defoe writes of desperate Londoners searching for answers by looking at patterns in the clouds. Pepys tracks the illness from before it even arrives in the city. Someday, your children and grandchildren might ask you what life was like during the great pandemic of 2020. What will you tell them? Unless you keep a journal or careful notes, you will get some things wrong. No matter how smart you are, and how dedicated to the truth, your memory will play tricks on you. Careful studies have shown that your mind can take what you read, or see on TV, or hear in discussions, and turn it into what seems to be memory. So start writing now about what your life is like during the time of Covid-19. These are historic times. To learn more about journal writing, let’s take a look at the arrival of the plague in 17th century London through the eyes of those who lived through it. Unlike Covid-19, which is a virus, the bubonic plague is a bacterial infection. Defoe writes that it "operated in a different manner on differing constitutions; some were immediately overwhelmed with it, and it came to violent fevers, vomitings, insufferable headaches, pains in the back, and so up to ravings and ragings with those pains." Plagues were not something new, but had recurred many times over hundreds of years. Europe had an especially bad outbreak, called the “Black Death,” in the middle of the 14th century. In congested cities, plagues spread rapidly. So, in 1665, Londoners are very aware that a big city is not a good place to be when there is a plague. For a long time, it was thought that this plague has arrived on fleas carried by black rats. But some research in recent years has diminished the role of rats and focused more on the fleas, as well as body lice. London’s streets in the 17th century are narrow and its buildings are over-crowded and dirty. Because of the frequency of plagues, most people know that they can spread person to person. The importance of social distancing is understood. Houses where someone has died are marked with a cross painted red and the words, “God Help Us.” Their doors are locked to keep the infected in and others away. Many head for the countryside. The people living there are not welcoming. Would you be? They fear that the city folks carry germs. Those that stay in London are mostly poor, or stubborn, and, if they survive, lucky. They are still dealing with the plague when a huge fire sweeps through London. Much of the city burns down, leaving its citizens to deal with a double whammy of disasters—though a lot of the plague-carrying rats do get fried. Daniel Defoe writes an account titled, “A Journal of the Plague Year, written by a CITIZEN who continued all the while in London.” It’s a riveting tale and a model of journal writing. Read it and you will get first person details of life during that pandemic. Defoe writes of “an abundance of people” fleeing the city. Some of those who stay behind try to find meaning for what is happening: in their religion, in their imaginations, or sometimes in the clouds. Of the cloud-watchers, Defoe says, “They saw shapes and figures, representations and appearances, which had nothing in them but air, and vapour.” Many are sure those clouds carry messages from the heavens. Defoe’s journal tells of cheats who promise cures for the pandemic to those who buy their miracle powders. “There is no doubt but these quacking sort of fellows raised great gains out of the miserable people…” “A Journal of the Plague Year” is written as if it is the diary of a man in his twenties who is living through the plague. Today we know that Defoe was five years old when the plague struck London. As a question-asking boy, he saw and heard unforgettable things. He turned those moments into a journal; it gives a detailed picture of London during the plague. But the reader has to guess what is truth and what is fiction. The 17th century literary world has few rules or boundaries, so that was not a big deal when the journal was published. It would be today. “A Journal of the Plague Year” is not journalism, it’s not even a personal journal. It is fiction based on memory. Another book that Defoe wrote, “Robinson Crusoe,” is said to be the first novel in the English language; it is based on a true adventure. I like Defoe’s work; especially his “Journal of the Plague Year.” It is a good model if you decide to keep a journal. But if you do, stick to the truth. That’s the point of keeping a journal. For a different view of the 17th century’s great pandemic, there is another journal. It is not fiction, it describes that same plague year, which its author, who is wealthy, sees from his own perspective. That book is “The Diary of Samuel Pepys.” Pepys (pronounced peeps) first mentions the plague in his diary when he learns that some people in Amsterdam are sick. That is in October 1663. He fears (correctly) that the plague might spread to London. When it does, he has the means to leave the city, but instead he stays and observes and writes. Pepys says things in his journal that he might not share with everybody. He is a Naval official and a member of Parliament who may have a natural immunity to the flea’s bite. He goes wherever he wishes and takes note of what he sees. He conducts his business and walks about town; he has an inquiring mind, he never seems to have sickened; instead he prospers during this time when most others have fled the city. Pepys’s journal will make him famous. Here is what he writes on September 2, 1666, the day a great fire takes hold: I down to the water-side, and there got a boat and through bridge, and there saw a lamentable fire. Poor Michell's house, as far as the Old Swan, already burned that way, and the fire running further, that in a very little time it got as far as the Steeleyard, while I was there. Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that layoff; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down. “But, Lord! how sad a sight it is to see the streets empty of people,” added Pepys, and we can only agree. Remember that even small details can enliven stories. You can write your journal on an electronic device or use a pen or pencil. Keep a record of what these times are like—for your future self and to share with others. Create word pictures of the year 2020 for those who aren’t here to see it. To do that well, it helps to write clearly. You don’t need fancy words or a lot of adjectives. You do need to observe carefully; also listen to what people are saying. Then describe this year in words that help your reader create mental pictures of what is happening now. You can be the author of your own story. |

These lessons are intended for your use at home. They are copyrighted by Joy Hakim and are not for commercial use or redistribution.

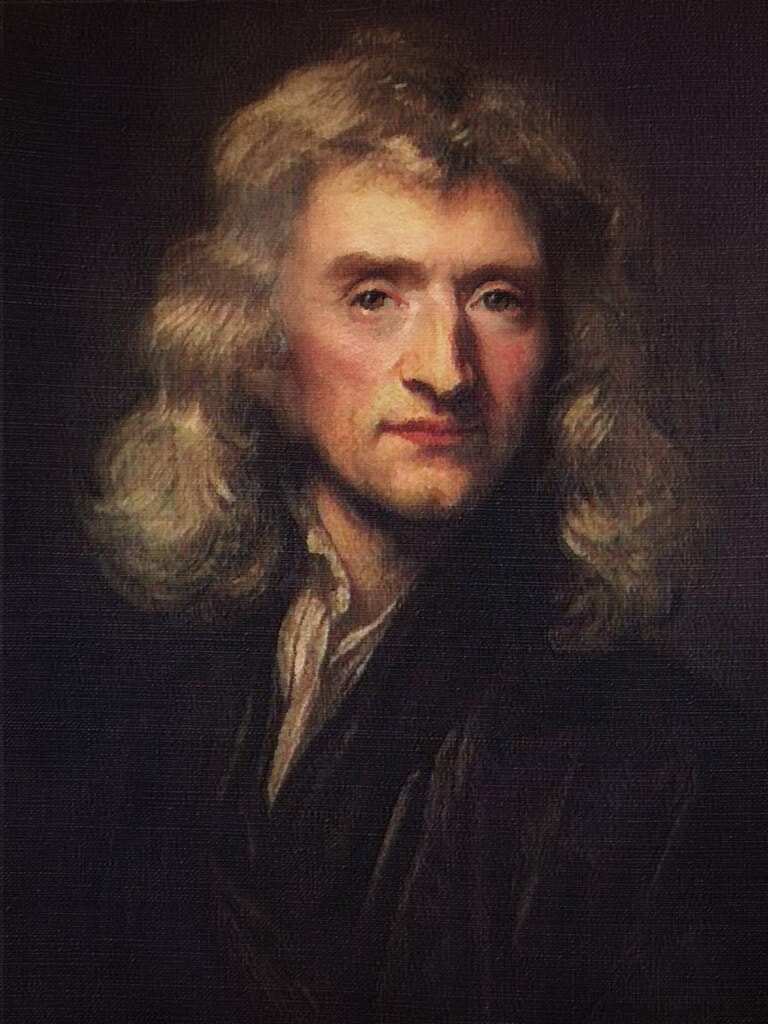

Newton During the Plague

Cambridge University sends its students home during the plague. One of those students, Isaac Newton, goes to his mother’s home at nearby Woolsthorpe. A two-story yeoman’s farmhouse it has a hayloft and a place where grain is stored. Newton isn’t much of a farmer, he has goofed up in the past, so his mother leaves him alone to do what he wants. He spends much of this at-home time searching for answers to big questions about the universe. He has inherited a large blank book from his stepfather; he will use it well. Newton will think about light and help found the science of optics. He will figure out calculus, a mathematical tool that, among other things, can calculate motion. He will come up with a formula for gravity. He pictures gravity as a force, his formula offers an easy way to figure its impact, but Newton knows there is something wrong with his picture. He tells his friend the Reverend Richard Bentley “that one body may act on another at a distance through a vacuum …is to me so great an absurdity, that I believe no man who has…a competent faculty of thinking, can ever fall into it.” Gravity an absurdity? These are Isaac Newton’s words.

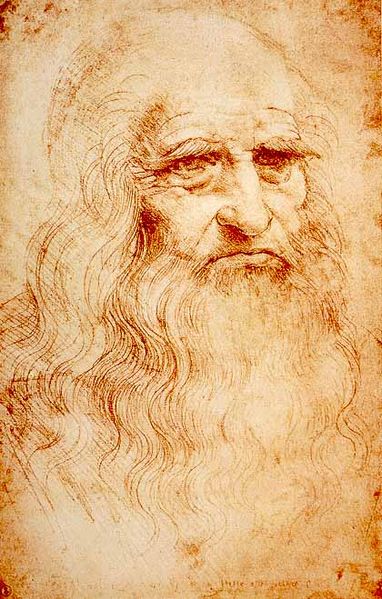

He goes further, “I have not been able to discover the cause of those properties of gravity…and I feign no hypotheses (he actually writes that in Latin: Hypotheses non fingo).” There’s still more in that letter to Reverend Bentley, “I have not yet ascertained the cause of gravity itself…Pray do not ascribe the notion to me.” Whew! That is Isaac Newton who is saying: don’t associate gravity with me. He won’t get his wish. But he is right; he doesn’t understand gravity. Albert Einstein will come along in the 20th century with a new theory of gravity, a theory known as relativity. When he does he will apologize to the memory of Newton. (If you are interested in some details check my book: Einstein Adds A New Dimension.) Leonardo da Vinci survived a series of bubonic plagues that struck 15th century Milan. That city was, hard to navigate, dirty and crowded—all of which made it ideal for the spread of disease. The outbreaks, between 1484 and 1485, killed some 50,000 people—a full third of the city’s population. They inspired the Renaissance polymath to design a future city; he pictured it in a series of drawings and notations completed between 1487 and 1490. Leonardo’s urban designs focused on cleanliness, beauty, and efficiency. He pictured a future city with a network of canals to support both commerce and sanitation. He divided his city into tiers, each meant for a different purpose. He intended that new cities be built at sites near large rivers, and that existing cities be radically rethought. His ideas went unrealized. Today, da Vinci’s thinking is being reexamined with new urban centers seen as havens from disease. And that is giving Da Vinci’s ideas currency in today’s world of landscape architecture.

|