LESSON 5

A Book That Costs Less Than a Cow: A look at Johannes Gutenberg and the history of printing presses - and a challenge to make a book of your own.

A Book That Costs Less Than a Cow: A look at Johannes Gutenberg and the history of printing presses - and a challenge to make a book of your own.

|

J

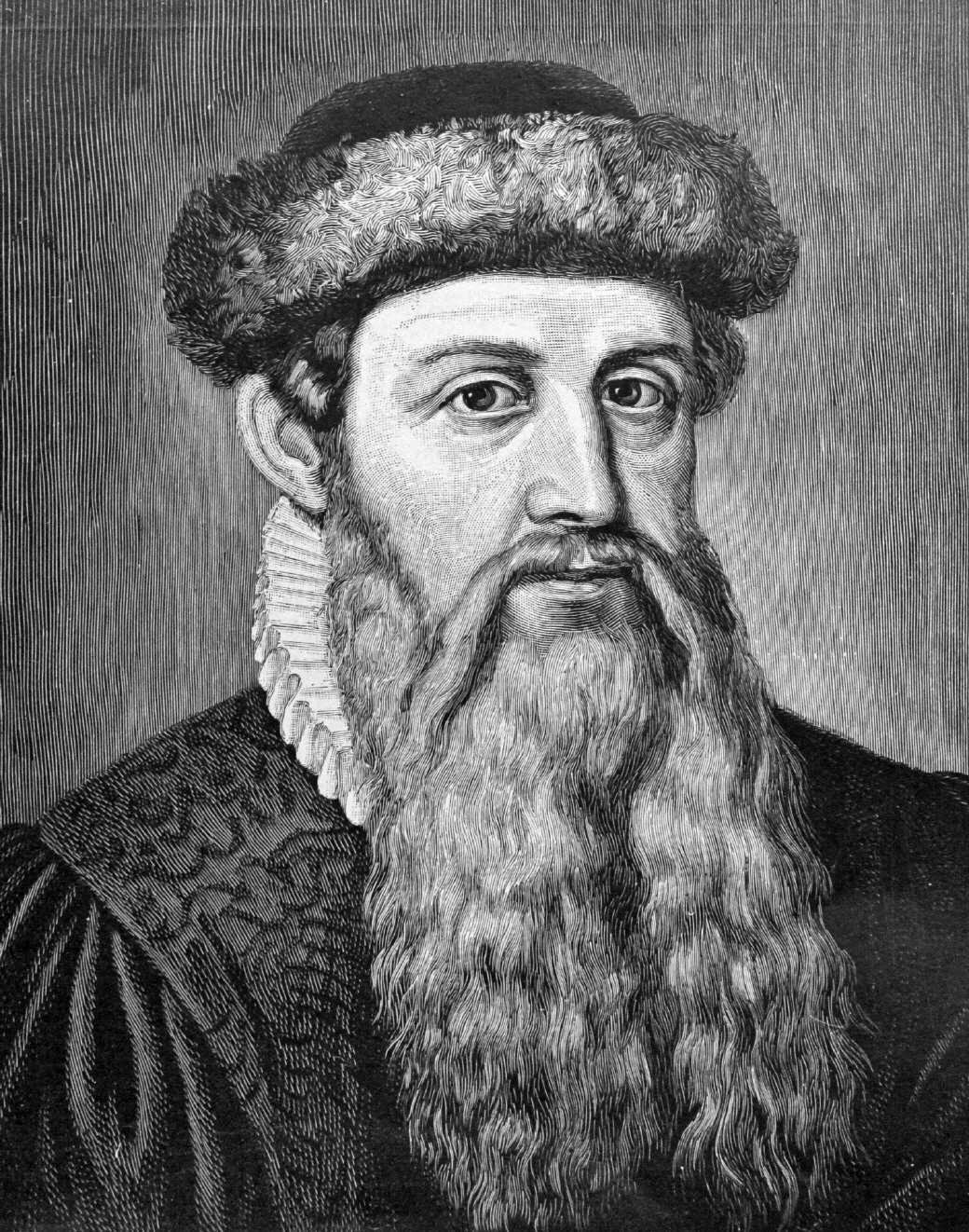

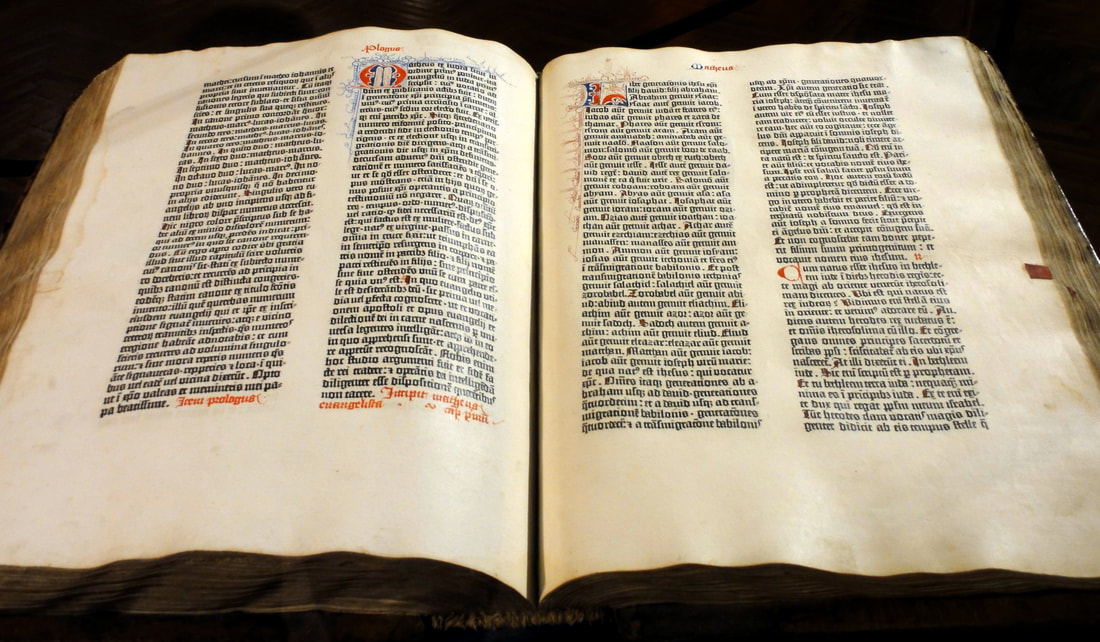

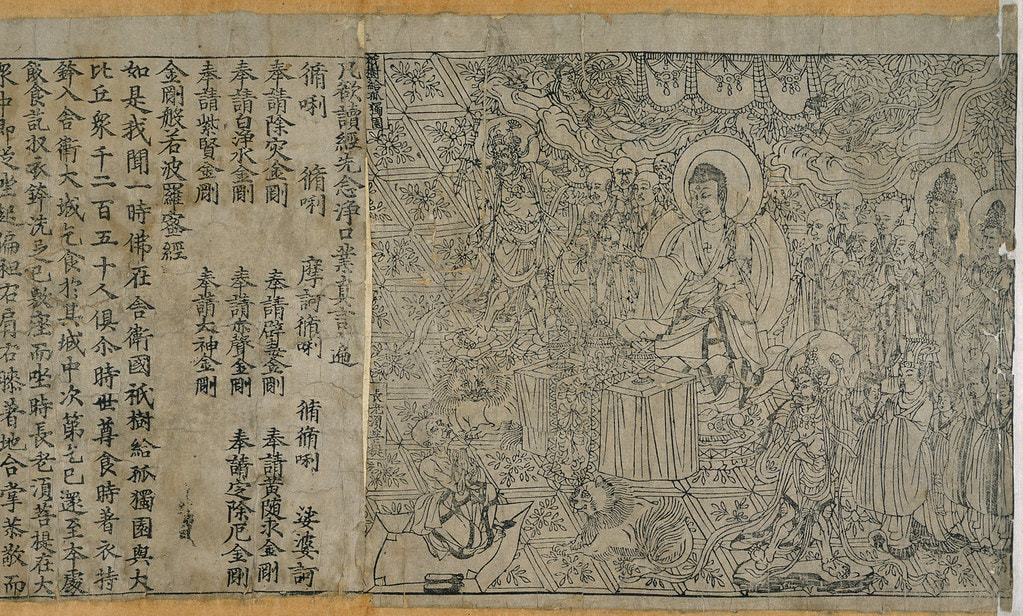

Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1397-1468) developed movable type in the mid-fifteenth century, beginning a process that made books easy to produce. And that helped create "a whole new Democratic world" where almost everyone could learn to read. You've probably heard that before but there's more to the story. At first, the Chinese wrote their books on wood or bamboo and then on rolls of silk. But silk was expensive and bamboo was heavy. So, sometime before 100 B.C.E., they began to develop a method of making paper from tree bark, hemp, rags, and even old fishnets. Some authorities say that Ts'ai Lun actually invented paper in 105 C.E. More than six centuries later, in 751, when the Chinese had perfected the process, some papermakers were captured by Arabs and brought to Samarkand (now in Uzbekistan in Central Asia). They taught their jailers how to make paper. After that, the secret was out and the art of papermaking spread west. But paper was only part of the process. Books had to be handwritten by copyists or scribes. You can guess how long it might take to make a book, especially if it had painted illustrations. So books were mostly for the very rich. When was the first book printed using a reproducible method (instead of handwriting)? No one knows. But in 1900 a Taoist (DOW-ist) monk accidentally found an ancient hidden library sealed off in an old cave in China. In it was a book made of seven huge sheets of paper joined together to make a scroll about 5 meters (about 16 feet) long. Six of the sheets were Buddhist teachings; the seventh was a picture of the Buddha. It had been beautifully printed from seven wooden blocks—and we know exactly when. The book, a work of Buddhist scriptures called the Diamond Sutra, had an inscription that read, "Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 13th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong." That date is May 11, 868. (Today, the British Library holds the Diamond Sutra.) Block printing was used even earlier as a way to print designs on fabric. The Chinese also used blocks to print money, which startled Marco Polo when he visited the court of Kublai Khan in 1275. "With these pieces of paper they can buy anything," wrote Polo in amazement. But books are something else. Carving a wooden block full of words (as was done with the Diamond Sutra), is a lot of work, and the block can't be used for any other book. There had to be a more efficient method-and there was. In the eleventh century, a Chinese artisan named Pi Sheng developed movable type. Since the traditional Chinese languages do not use an alphabet, Pi Sheng had to find a way to cut word symbols, called ideograms, onto pieces of wood and then line up those wood pieces in a frame that could be inked, used as a printing block, and later taken apart so the ideograms could be reused. It was more complicated than you might imagine. Suppose he wanted to include a picture in that frame? Remember: everything had to be level so it would print evenly. Pi Sheng did it. In Korea, 200 years later, handsome books were produced with movable bronze type. Metal type doesn't wear out as quickly as wood type does, and it can be cast with delicacy and precision. Printing was being refined in the East. At the same time in Europe, books were still printed from single carved wooden blocks, much as the Diamond Sutra had been printed. So why does Gutenberg get so much credit? Because printing as Gutenberg developed it was more sophisticated and efficient than anything done before anywhere. The cost of books would plummet. Gutenberg didn't just make printed books. He produced gorgeous books—books as splendid (or close to it) as the hand-illuminated manuscripts that scribes and artists had been creating in Europe. To do that took the work of a genius. We don't know a lot about Gutenberg, but we do know he was a litigious (li-TI-jus) figure. The first time he turns up in court records is when a woman sues him for breach of promise. She said he promised to marry her. He said he didn't. He won. After that there are years of lawsuits relating to his print shop and the financing of his invention. What those lawsuits tell us is that this man is persistent—he doesn't give up. That persistence is a necessary part of being an inventor. Gutenberg faces four problems in devising a method for mass-producing books. He needs to design letter type itself, as well as a matrix to hold the letters in place. He needs to find a new kind of ink that can be applied easily and will reproduce uniformly. He needs to find paper that will absorb the new ink. And he needs to design a mechanical method of printing to replace the old method of hand-pressing each individual sheet. He does all those things. It is the work of many years. When it comes to printing, Gutenberg has a big advantage over the Asians. The Latin alphabet has only 23 letters (w, k, and y are missing in Latin). When you add punctuation marks, capitals, and other symbols, it adds up to about 150 characters. In contrast, Chinese has about 30,000 characters. The challenge is different. Chinese ideograms are relatively large; Roman letters are usually small. Gutenberg has to make sure that every metal block with an A, for example, is interchangeable with every other A block. The letter X is larger than I—so how can they both fit in the same matrix? His skills as a goldsmith and metal caster (which is what he was before he became a printer) are invaluable. One of Gutenberg's most important inventions is a mold for casting type quickly. It is a machine tool—an early step in the process that will soon allow machines to do more and more jobs of human workers. No Chinese or European (as far as we know) had used a press for printing before Gutenberg. Presses were used for other purposes: They extracted juice from grapes to make wine. They were used to bind books. Gutenberg decides to design a press for printing. But the ink used by scribes won't do. He has to come up with a better type of ink. Flemish painters are experimenting with pigments that have linseed oil added. Gutenberg devises an oil-based ink. Then he designs paper that will absorb the new kind of ink. Other design hurdles loom. All this takes years and a lot of money. Finally, in 1445, he prints his first book, a Bible. It is gorgeous, the work of a perfectionist. Back in eighth-century Spain, a book cost about the same as two cows. (A cow was as valuable as a car is today.) By Gutenberg’s time—the first half of the fifteenth century—hand-copied books are even more expensive, often costing several ounces of gold. That helps explain why most people are illiterate. Learning to read isn’t worth the bother if you can never hold a book in your hands. Even college students, who are literate, learn by listening to lectures and taking notes, not by reading. Books are just too expensive for all but the very wealthy. Gutenberg’s new system spreads books like leaves in a windstorm. Printers are soon turning out inexpensive, mass-produced volumes. And they cost a whole lot less than a cow. |

Johannes Gutenberg

Reprinted from the ebook "Reading Science Stories." These lessons are intended for your use at home. They are copyrighted by Joy Hakim and are not for commercial use or redistribution. A Gutenberg Bible

The Diamond Sutra of 868 AD, from the British Museum

Printing press from 1944

An assignment: I hope this story gets you to appreciate books. Even better, since you are working at home, how about writing one? I'd suggest that you start your career as an author with a book for a first grader you might know. Make it a nonfiction book, in other words, about something real. Choose a subject, then do some research and see if you can discover things you didn't know about your subject. Keep in mind: you need to make it easy to understand, so keep your words simple. But you do not need to make the subject simple. The 7-year-olds that I know are amazingly smart and informed. As a published author, my experience tells me that to make your book any good, you will need to write more than one draft. I do a whole lot of revisions. I reread what I've written, I think about it, I share it with others, and I rewrite. And rewrite. Each time my writing seems to get better. You will need to do some things I don't do. Illustrate your book: with your drawings or with pictures you find elsewhere. Put it all on pages that can be bound and turned. Have fun, but do a good job, find a 7 year old reader (if you can't find one, a grandparent may do). |